Island

July 2020: Michael's email michaelgalbreth@gmail.com has been hacked. Any messages received from that email are illegitimate.

Quirk of Mind

"The ability of those able to understand post-Schoneberg music is due to their possessing a particular quirk of mind that enables them to grasp modern music." – Noam Chomsky

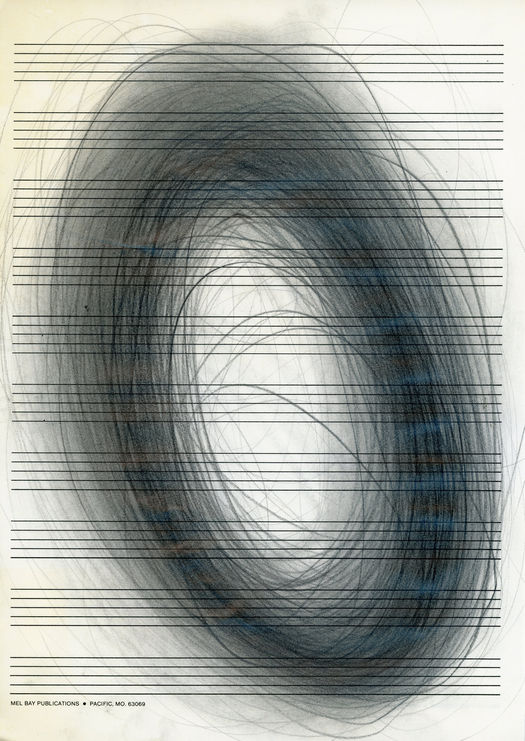

untitled, 1985, graphite on music score sheet paper, 11 x 8.5 inches

I am the fortunate recipient of innumerable discoveries, those moments of enlightened learning that occur in one's lifetime that feed the mind. They have arrived in equally innumerable forms from a vast array of experiences, sources, and people. As pleasurable and rewarding as they may be, they are not often true surprises. Discoveries are what inevitably happen if one is out poking around, looking under rocks. I do that. But I can count on one hand the number of epiphanies I've had in my life. What I call an epiphany is that unrequested lightening bolt from a clear blue sky that shocks you off your horse and converts you to a new way of seeing that you didn't even know existed. Two of those happened on the same day.

_______________________________

Concert for New Music America 1985, November 5, 1985, Los Angeles, California, approximately 7:30 p.m.

Having arrived early, I found a good seat on the upper level near the center of the auditorium. I was there to attend an evening of performances at the Japan America Theater (now known as the Aratani Theater) in the "little Tokyo" section near downtown. The concert was scheduled on a Tuesday night midway through New Music America 1985. This version of New Music America, the 7th, was being held that year throughout Los Angeles. More than just an interested audience member, I was there to observe the festival as the incoming organizer of New Music America 1986 scheduled for Houston the following April.

The program for that evening was a mixed bag of very different kinds of music. Included on the program were Morton Subotnik, Christian Marclay, the John Carter Quintet, The Fibonaccis and Daniel Lentz.

I knew of Marclay's work, which then consisted mainly of performances using vinyl LP's spun chaotically in an energetic spasm of turntable-ism, sometimes utilizing homemade guitar/record-player hybrid instruments played in a rock band format. Christian's stuff pre-dated the hypno-techno DJ dance club scene, but post-dated the punk breeze, and therefore fit neatly within neither of those nor much of anything else. Subotnik was famous in the experimental music world having co-founded the California Institute for the Arts (CalArts). Before that he co-founded the San Francisco Tape Music Center along with Pauline Oliveros. (As it turned out, I was working with Pauline on New Music America 1986, for which she was the Artistic Advisor.) Subotnik was the quintessential electronic music wizard. I was already familiar with his music, most especially through his landmark "Silver Apples Of The Moon." I had heard of both John Carter and the Fibonaccis, but I only had a vague idea about their work. The Fibonaccis represented the "art rock" genre that was popular then. It wasn't quite a rock band, nor a performance art group, but rather a sprinkling of both. Carter's music fit within the vast and varied domain of "jazz" (Scare quotes are necessary because I'm still not sure anyone really knows what jazz is. Unfortunately, the term long ago lost any immediacy, just like Dada, with which, not so strangely, jazz is linked.) On the jazz spectrum, Carter's music leaned toward the polite side, opposite renegades like Ornette Coleman, a former school chum. I knew nothing about Lentz. This concert would be the first time for me to experience any of these composers' works live.

(L. to R.) magazine advertisement for New Music America 1985,

opening ceremony for New Music America 1985, Los Angeles City Hall

_______________________________

Asheville and Nashville, 1964-1974

I watched The Beatles on our black-and-white console TV when they performed for the first time in America on the Ed Sullivan show on February 9, 1964. I was eight years old. Like all of those millions of other American kids who watched too, I fell in love with them and their music. The first record I ever bought was a 45 RPM of "She Loves You." I played it repeatedly until the memorized sound had deteriorated into barely more than a scratchy hiss.

In 1964, when I was ten, my family moved from Asheville, North Carolina to Nashville, Tennessee (with a brief five month detour in Houston in between). I grew up in Nashville as part of a middle class family in the suburbs on the west side of town. There were no galleries or museums in Nashville at that time so I never went to one. Although I grew up in Nashville, I detested country music. (I still hate it.) The only concert I ever attended before college was in 1973 to see Elvis (last name unnecessary). By that time, just a few years before his death, his performances devolved into semi-coherent wanderings on stage between songs clad in winged rhinestones (avec Belt) picking up roses and bras strewn everywhere. One didn't go to hear Elvis, but rather to say that you had seen him.

Elvis performing in concert, July 1, 1973, Municipal Auditorium, Nashville, Tennessee

Growing up in Nashville, the only time I saw a symphony was when the local orchestra visited my high school and performed in the decaying parquet-floored gymnasium. I don't remember the program or the music that was played, but I remember not being very interested. During grammar school, my idea of music was whatever Top 40 pop song was playing on AM radio. Later, in high school, it was whatever rock and roll song that was playing on FM radio. My taste in music was not sophisticated, and although I enjoyed music immensely like everyone else, it wasn't an obsession. Music was entertainment. The concept that music could be an intellectual pursuit was an alien thought.

_______________________________

Concert for New Music America 1985, November 5, 1985, Los Angeles, California, approximately 8:00 p.m.

(right) cover of High Performance Magazine #31/ New Music America 1985 catalog

(left) highlighted concert listing for Tuesday, November 5 at the Japan America Theatre

In the High Performance magazine (issue #31) that doubled as the catalog for the 1985 New Music America festival in Los Angeles, there is a brief listing of the program for that Tuesday evening's performance. There is no mention of the titles of the pieces performed by the John Carter Quintet, the Fibonaccis or Christian Marclay. Morton Subotnik's composition is listed as "The Key to Songs" performed by the California E.A.R. Unit. Daniel Lentz's composition is listed as "Bacchus" as performed by himself, Tom Recchion, and Christian Marclay.

The set-up for "Bacchus" caught my eye. It seemed familiar. On stage were music stands corresponding to each performer -– Lentz, Marclay, and Recchion – with a table of electronic equipment adjacent to them and off to the side. The performers took their places behind the music stands each holding a glass of wine. I sat up. And they began...

As the performance progressed, I could barely sit still. Grinning ear to ear, I watched and listened. Finally, finally, here it was. I could hardly believe my ears. I nearly wept.

Later that evening, I was seated at a large table among many others at an after-concert gathering. Around me were Morton Subotnik, Joan La Barbara, Carl Stone, and Daniel Lentz. Everyone seemed to know one another and the banter was lively and friendly. Carl and Joan were the artistic directors of New Music America 1985. I was the newcomer and outsider of the group. The only justification for my presence was that I was the organizer of the next New Music America festival. Other than that, no one knew who I was or what I did. I was the quintessential unknown new kid on the block. Although up until that moment I had remained mostly silent in deference to my esteemed conversationalists, and pretending not to be intimidated, I was nevertheless anxious to speak. In the normal ebb and flow of a party-like discourse among this illustrious group, there was a lull.

"Daniel, may I tell you a story?"

Everyone's gaze shifted toward me.

_______________________________

October, 1976, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

After two years of college, I had had enough of school. I needed a break. So I teamed up with my high school chum, Mike Hooker (aka "Hook"), on a quest to see at least part of the world. Like many young Americans in those days, dressed in blue jeans and flannel shirts, armed with Eurail passes and tickets on Icelandic Airlines, we flew across the Atlantic for a revelatory trek across Europe living as close to the $15-a-day budget we read was possible. We spent three months traversing the continent, riding the rails from Oslo, to Madrid, Istanbul, Sicily, Paris, and more. Throughout our journey, I dragged Hook along with me to all of the art museums. More than just an obligation for young artists, going to museums is what almost all tourists did. Part of the reason for visiting foreign countries, of course, is to absorb the culture. Since art museums are where societies store and display examples of culture, that's where we went, just like everyone else. The difference was that I went there to see the art. Hook patiently went for the experience of having seen it.

The museums in Amsterdam are clustered in close proximity in the center of the city, conveniently located near the red light district. We went to all of them (the museums, that is). First we went to see the Dutch stars Rembrandt and Van Gogh at the Rijksmuseum and Van Gogh Museum respectively. By then I had two years of art history under my belt which consisted of generalized overviews ranging from the Lascaux caves to Pop art – extremely broad and equally shallow. I was keen to see with my own eyes those works that the learned Janson assured us were great. I saw everything, inspecting each painting closely (they were almost all paintings) with the comparative gaze of, "Could I do that?", not so much technically, but more so as, "Could I independently come up with something like that?" I don't know what I expected to see or think, but I had no feelings of awe, and certainly none of confusion. I can't say it was all a let down, but there were no enlightened "ah ha's" either. It was mostly a, "Yup, that's it," shrugged reaction.

After digesting the hazy varnished chiaroscuro of Rembrandt and the psycho impasto of Van Gogh, Hook and I headed over to the Stedelijk. By that time I was somewhat visually fatigued and was not particularly excited. We started our visit on an upper floor. A staircase emptied out to a large turning corridor leading to some galleries. Upon the walls of this twisting hallway were various paintings hung intermittently. I turned the corner.

Robert Rauschenberg, CHARLENE, 1954, Combine: oil, charcoal, paper, fabric, newspaper, wood, plastic, mirror, and metal on four Homasote panels, mounted on wood with electric light,

89 x 112 x 3 1/2 inches (226.1 x 284.5 x 8.9 cm), Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

_________________________________________________________

You Can't See the Forest... Music

Daniel Lentz

1971

4:00

for three speaker-drinkers with three wine glasses (with mallets) and red wine

speaker-drinkers: Daniel Lentz, Garry Eister and Stan Carey

cascading echo systems: Daniel Lentz

©1984 Lentz Music (BMI)

_______________________________

November 5, 1985, Los Angeles, California, approximately 10:00 p.m.

I concluded:

"That was you, Daniel. That was you that day in Amsterdam in that performance. That performance changed my life. I had begun to believe that I made it all up somehow in my head and that it never happened. Until tonight when finally at long last, once again, I heard that piece of music. And here you are right here in front of me. So that's it. That's my story. And I'm pleased to finally once again hear the music, and to meet the person who helped me to hear music for the first time."

My table mates seemed pleased with this story, if not surprised and charmed. Daniel especially so. As with all lively gatherings, the participants eventually dissipated away. The rest of my evening and time at New Music America 1985 was spent with others at other events. I never saw Daniel Lentz again.

Through my own work, and perhaps most especially because of my association with New Music America throughout the 1980's, I came to know virtually everyone in the relatively small and specialized sphere of experimental music. Of all of those people, and of all of those concerts and events, my very brief brush with the composer who changed how I heard and thought about music remains among my most cherished life experiences.

Dear god.

Conjure any cliché of awestruck dumbfoundness you wish, then multiply that by any factor. What was this? "What?" Blinking. Head shaking. I did not know what to say or think. I turned to Hook.

"I think I've seen art for the first time."

Hook knew what I meant but he didn't see it himself. I knew this work, I knew this painting, I knew what it was about. And for the first time in my life, a real, honest-to-god piece of art hung right there in front of my nose. I had seen reproductions of Rauschenberg's work, but they were like any other reproductions: just images on a page, too small and flat to make any impact. But this... This wasn't just a painting. This was... actual. Suddenly and emphatically, this was a PAINTING. Yes, technically it was a painting because there's paint there. But it wasn't used in any way that I was used to. It was applied almost as a tongue-in-cheek nod to art history while simultaneously casting all that aside. This wasn't a landscape, a street scene. This was the street – torn, shredded, nailed, stretched, glued, arranged in a broken grid, dissembled and then reassembled. You could smell it.

I stood there for the longest time, just looking. Close up, far away, from the side, then the other. There were no museum guards to chase me away so I stood within inches of it, so close I could have licked it. I examined it, soaked it in, and taking in every detail, I tried to memorize it, which is an impossible task for that object. And if one "read" it, left to right, top to bottom, it starts out, roughly, with a lit light. Then there's the wicked coup de grace of a joke: a mirror, as if in a final winking, "Here's looking at you, kid." All of this, all of this and more in one instant knockout punch of a glance. Wham.

Finally at long last, we had to go.

Downstairs and adjacent to the main entry hall of the museum was a big room. It was a relatively nondescript room, one of those multifunctional spaces where lectures, performances, receptions or anything else could take place. It was just a big box. Several rows of folding chairs were set up for an event of some kind. At the entry was a notice, a poster advertisement, something about music. Having nothing better to do, a little art weary and still recovering from the shock of the Rauschenberg, we sat to rest and have a listen.

Four people entered the room, dressed formally in black, three men and a woman. The woman and two of the men stood before microphones and music stands upon which rested a glass of red wine and a score. Off to their side, stage left, sat another man behind a long folding table upon which were open-reel audio tape machines and some other things that I can't recall. It was then that I noticed that the audio tape from the machines stretched out from the machines on the table, looping across the room, suspended by something or other, then finally returning back to the tape machines. What kind of kooky setup was this? Then they commenced.

Starting with the performer on the end they began. The first person, holding a glass of wine in one hand and what appeared to be a small mallet in the other, voiced a vowel or consonant sound, nothing more than an utterance, into the microphone, took a sip of wine, then softly clinked the glass with the mallet. Ding. This was immediately followed by the next performer who repeated the action but with a different utterance. Then on to the next person, and the next, proceeding in order and down the line.

AH (ding) T (ding) K (ding) EE (ding) T (ding) S (ding)

Then pause, and silence for a few moments. Their recorded voices, encoded onto the magnetic tape, made its way around the room and was replayed back through speakers. Then they started again, repeating their actions but this time with a different utterance each so that their live voices and sound of dinging glasses were combined with their recorded utterances and dinging from before. Then they did it again. And then again. Around and around they went, one, two, three in rote fashion, one after the other. These jumbled bits of voice sounds overlapped the ting-tong-tangling of varying pitches of the glasses of wine, and continued for several minutes in a seemingly uncoordinated dissonance. Yet it was planned and organized because the performers were reading from the score in front of them while the other person tended to the recording and sound equipment. There was a method.

What were they doing?

U (deng) NT (ding, deng) EE (deng) E (deng) FO (deng) R (ding) ST (ding) R (deng, ding) TH (deng) S (ding)

It continued with more voice sounds, more dinging, more playback of more voice sounds with more dinging and on and on. As the wine lowered in each glass, the dinging of the glasses from the mallets changed pitch becoming deeper and lower. If the sound could be written, it started as "ding," then slightly lowered to "deng," continuing to the lowest "dang." The seemingly disconnected vocalization of vowels and consonants began to build, to collect, reassembling themselves first into syllables, then slowly, mysteriously, and most weirdly, into what sounded almost like words. As it progressed, these connected themselves again. Were these phrases? As the sounds accumulated, you could begin to make it out, but because each utterance was made by a different person, each word was an audio assemblage of separate voices, and those utterances were accompanied by tinkling sounds of varying tonalities.

Y (ding, dang) U (deng, ding) C (ding) NT (deng) SEE E (dang, deng) FOR (deng) ST (ding) F (deng) R (ding, dang) THE (ding) TR (deng) S (dang)

Ever so slowly but unsurely, six barely distinct cliche´s revealed themselves...

"There is a pot of gold at the end of every rainbow"

"Don't put the cart before the horse"

"Better late than never"

"Never cross the bridge until you come to it"

"Birds of a feather flock together"

Culminating, at long last, with the final phrase...

YOU (ding, deng) CAN'T (dang, deng, ding) SEE (ding) THE (ding, dang) FOREST (ding) FOR (ding, deng, dang) THE (dang,ding) TREES (deng)

End. Applause. Bewilderment. Amazement. Transcendence.

It was collective spoken voice, but it wasn't exactly speaking either. The robotic dissonance wasn't a racket, but it wasn't melodious either. But it was altogether fascinating, and right there in front of my ears. Prior to that performance, I couldn't hear sound for the music, and vice versa. Suddenly and most permanently, everything changed. For the first time, I felt time. Time had been captured, moved, rearranged, and then reassembled. I understood music structurally. Music is time.

I was absolutely, flabbergastedly stunned. Yet everyone else in the museum was just walking around, calmly, as if everything were normal, everything was okay. But for me, it suddenly wasn't. In a flash it had all changed and things were decidedly not normal. In my mind I wanted to shout, "Hey, everybody. This. This!" From that very moment on, I would never hear or experience "music" the same way again.

I was too bowled over to document the event – its title and participants. I later regretted this carelessness as I couldn't remember who it was that I saw, or exactly what it was that I heard. I was left with only the memory of it. For years I replayed this performance over and over in my head. Up to that point, having nothing with which to compare it, I had a hard time understanding what it was. After a while it became a myth in my mind. I kept asking myself, "Did I really see and hear this?" and "Who was this?" until I began to think I dreamt it.

"You Can't See the Forest...Music" by Daniel Lentz

performed solo by Brady Harrison, with digital electronics and water, 2014

Percussive Arts Society's International Convention

November 21, 2014, Indiana Convention Center.

__________________________________

October 5, 2018